Eugen Weber, France: Fin de Siècle -- Female Underwear and Personal Hygene

More interesting, as bulky petticoats and panniers ebbed, other articles of underwear acquired more importance. Octave Uzanne, writing in 1898, felt that the special characteristic of contemporary women was the luxury of their underwear-- considerably developed in the past fifteen years, "in response to the severity, the simplicity, the sobriety of outer garments," and especially of the "English costume, the costume tailleur." Having abandoned outward ostentation (Uzanne exaggerated a good deal, but his standard of comparison remained the crinoline!), all jolly luxury now took refuge with the undies. So apparently did color, which a chronicler of 1896 interpreted as a recent "modern taste, born no doubt of the nervousness that torments our imagination."

Such male views seem to be confirmed by an article of the same year in La  Nouvelle Mode, which referred to the current efforts to render underwear "as little voluminous as possible-given the fashion of ever more clinging skirts. A whole school of very elegant women who count the millimeters of their waists and the centimeters of their hips" has managed to combine chemise, drawers, and small underpetticoat into a single garment made of cambric or, if one were chilly, of China silk. This was the combinaison (combination), imported from the United States. The corset went directly over it, the underskirt was buttoned onto the corset, a little cache-corset in lawn (fine linen ) went over the lot, then everything was ready for the dress. "It is difficult to dress more lightly," La Nouvelle Mode opined, but ladies given to chills had better avoid such excessive divestiture. It is clear from this that simplification was relative, and that the silks, cambrics, and fine linens offered plenty of opportunity for creativity.

Nouvelle Mode, which referred to the current efforts to render underwear "as little voluminous as possible-given the fashion of ever more clinging skirts. A whole school of very elegant women who count the millimeters of their waists and the centimeters of their hips" has managed to combine chemise, drawers, and small underpetticoat into a single garment made of cambric or, if one were chilly, of China silk. This was the combinaison (combination), imported from the United States. The corset went directly over it, the underskirt was buttoned onto the corset, a little cache-corset in lawn (fine linen ) went over the lot, then everything was ready for the dress. "It is difficult to dress more lightly," La Nouvelle Mode opined, but ladies given to chills had better avoid such excessive divestiture. It is clear from this that simplification was relative, and that the silks, cambrics, and fine linens offered plenty of opportunity for creativity.

They also provided an open invitation to greater cleanliness, which seems to have counted among the rarer refinements of the modern age. Octave Uzanne, writing in 1894, noted the novelty of the concern "for the most intimate cleanliness" shown by fashionable women at least, for it went a long with luxurious lingerie. Was his observation representative? It was certainly new. We have seen that people were grubby, did not smell sweet, nor seemed much to mind it. As the proverb had it, the more the he-goat stinks, the more the she-goat loves him. That this could also work the other way is attested by frequent references to that odor di femina, the effluvia of armpits, and so on, supposed to drive men mad with passion. But even among the more sedate, shortage of water and feminine modesty long combined to make washing rare. A manual of elegance for ladies ordered its readers to shut their eyes while washing their private parts. This cannot have been a serious concern, since thorough ablutions were largely left to women of ill repute. Most of the rest followed the medieval Salernitan precepts of hygiene: "[Wash] the hands often, the feet rarely, the head never." Forain's sybarite affirmed that, whether he needed it or not, he always took two baths a year. Few of his fellow French of either sex could claim as much, and a fewyears before 1914 the father of a boarder at the lycée of Aurillac (Cantal), learning that his daughter attended the public baths weekly with her fellows, wrote a letter of protest to the headmistress: "I didn't entrust you my daughter for this!" Yet even such a letter is evidence that cleanliness forged ahead-- slowly, like everything else, hesitating before established prejudice reinforced by antediluvian facilities. Nevertheless, it pressed forward impelled by new medical and didactic norms, by the dictates of fashion, and by the rules of conspicuous consumption that made freshly washed linens a rare, hence desirable, luxury.

Two items among those listed by La Nouvelle Mode also became the subject of further evolution, along with much debate. One was drawers, or underpants, also known as tubes of modesty. Drawers had been a novelty, imported from England at the beginning of the century to beworn by little girls, whose skirts were shorter, and left to them for threescore years thereafter. At mid-nineteenth century, underdrawers did not figure among the items in a proper young bride's dowry. But the crinoline, with the mishaps to which it was prone, encouraged sporadic adoptions. Adding to the undergarment jungle, drawers were awkward, and the slits they occasionally had made them potentially more indecent than their absence would have been. This may bewhy prostitutes were quick to adopt them-a further argument against their being worn by honest women who, when they did wear them, preferred the closed model, buttoned at the side. Still, in certain circles drawers were considered symbols of purity; by the 1880s many well brought up girls were wearing them, at least in Paris. In 1892 Yvette Guilbert was singing

Two items among those listed by La Nouvelle Mode also became the subject of further evolution, along with much debate. One was drawers, or underpants, also known as tubes of modesty. Drawers had been a novelty, imported from England at the beginning of the century to beworn by little girls, whose skirts were shorter, and left to them for threescore years thereafter. At mid-nineteenth century, underdrawers did not figure among the items in a proper young bride's dowry. But the crinoline, with the mishaps to which it was prone, encouraged sporadic adoptions. Adding to the undergarment jungle, drawers were awkward, and the slits they occasionally had made them potentially more indecent than their absence would have been. This may bewhy prostitutes were quick to adopt them-a further argument against their being worn by honest women who, when they did wear them, preferred the closed model, buttoned at the side. Still, in certain circles drawers were considered symbols of purity; by the 1880s many well brought up girls were wearing them, at least in Paris. In 1892 Yvette Guilbert was singing

Ell'n'voulait pas avant l 'mariage

Quitter ses pantalons fermés;

Ça vous prouv'bien qu'elle était sage,

Sa mère ayant su Ia former.47She never dreamed before her wedding

To yield th' impenetrable pantaloon;

It goes to show she was a good girl:

Her mother taught her not to spoon.

It is not clear how many women continued to wear drawers once they were free to go without them. A student of the question in 1906 believed that many among the bourgeoisie did not; and that "women of the people" never had. One of Colette's heroines explained that she preferred to feel her thighs soft against each other when she walked. More basically, as four young washerwomen tried in 1895 for flaunting themselves a bit too visibly declared: "Your Honor, it costs too much!" Before underpants really caught on with women, skirts had to get a good deal shorter, and this they did not begin to do till 1915. On the other hand, if underpants took their time, overpants appeared as early as the 1880s. We shall learn about this in due course, à propos the bicycle. But all seem to agree that cycling costumes affected fashion considerably. They probably furnished one more argument for wearing drawers. But they also put many young women into breeches, bloomers, and other sporting gear, taught them the convenience of pockets, spared them the need to raise their skirts, and gave them a taste for costumes in which they could sit, walk, or lean back more easily-- let alone pedal.

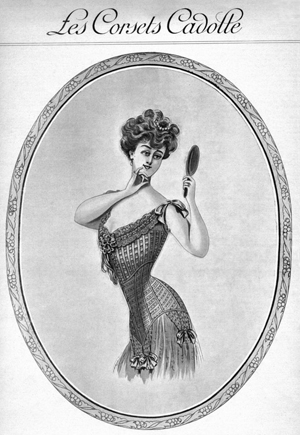

Above all, they helped to free women from the corset, or at least they set them on the road to freedom. If pants were a luxury, and a dubious one at that, corsets were regarded as a necessity at almost all levels of society. "A self-respecting woman," Fin de Siècle decreed, "must have a morning corset, a dress corset, and a bathing corset." This last, in heavy tulle or some light tissue, stiffened only with light stays, should still be strong enough to squeeze the waist tightly beneath the swimming suit. Corsets were big business. Under the Second Empire Paris had counted over 10,000 women corsetmakers, selling about 1,200,000 corsets every year for as little as 3 to 5 francs or as much as 200 francs, for a general turnover of more than 10 million francs. All this for the capital alone, where the relevant figures had grown by about one-third at the turn of the century; it would have been still higher but for the new disfavor with which the garment met.

Colette recalls "the time of the great corsets which raised the breasts high, crushed the behind, and hollowed out the stomach." Germaine Gallais, a contemporary actress, never accepted a "sitting" role. Sheathed by a corset that began under her armpits and ended close to the knees, two flat steel springs in her back, two others along the hips, a cord between the legs maintaining the edifice that was held together by six meters of stay lace, she stood up, even during the intervals, from 8:30P.M. to midnight.

Even less majestic structures could be a torture to wear and a menace to  the innards they compressed. Women would hide in the shadows of theater or opera box to slip off their corset, roll it in a newspaper, and breathe more freely; but many had no opportunity for relief. This mattered little apparently, until the cycling fad emphasized the corset's constriction and led thousands of young women to rebel against a grave impediment to their liberty to pedal. One cycled best in trousers, and trousers preferred no corset. Even without trousers, constrictions made pedaling difficult. The journal of the Touring Club de France in 1895 advised its women readers to abandon the traditional corset for a more rational foundation garment and, if they needed it, a brassiere. Riding bicycles had already revolutionized fashion, argued Dr. GacheSarraute. If it could lead to corset reform as well, it would benefit all humanity. The corset hampered women's breathing, their digestion, and ultimately their fertility, placing them in "an unjust and illogical state of inferiority." Dr. Gache-Sarraute was right, but the benefit she sought, like many others, was slow to come about. Medical theses were still arguing the case against the corset shortly before the First World War. The corset, Dr. Ludovic O'Followell affirmed in 1908, caused nervous dyspepsia, insomnia, heartburn, and, through the cordials taken to relieve this last, could lead to insidious alcoholism. It also occasioned "all those bothersome gurgles" that sometimes rose to t he level of "sinister plashings that spring from the depths of your stomach and make you pale and shudder with shame and horror." In this time of feminine revindications, opined O'Followell, when the natural being revolted against the conventions that deformed it, the corset, symbol of slavery that "add[ ed] to the natural inferiority of women," was "a new Bastille to be demolished."

the innards they compressed. Women would hide in the shadows of theater or opera box to slip off their corset, roll it in a newspaper, and breathe more freely; but many had no opportunity for relief. This mattered little apparently, until the cycling fad emphasized the corset's constriction and led thousands of young women to rebel against a grave impediment to their liberty to pedal. One cycled best in trousers, and trousers preferred no corset. Even without trousers, constrictions made pedaling difficult. The journal of the Touring Club de France in 1895 advised its women readers to abandon the traditional corset for a more rational foundation garment and, if they needed it, a brassiere. Riding bicycles had already revolutionized fashion, argued Dr. GacheSarraute. If it could lead to corset reform as well, it would benefit all humanity. The corset hampered women's breathing, their digestion, and ultimately their fertility, placing them in "an unjust and illogical state of inferiority." Dr. Gache-Sarraute was right, but the benefit she sought, like many others, was slow to come about. Medical theses were still arguing the case against the corset shortly before the First World War. The corset, Dr. Ludovic O'Followell affirmed in 1908, caused nervous dyspepsia, insomnia, heartburn, and, through the cordials taken to relieve this last, could lead to insidious alcoholism. It also occasioned "all those bothersome gurgles" that sometimes rose to t he level of "sinister plashings that spring from the depths of your stomach and make you pale and shudder with shame and horror." In this time of feminine revindications, opined O'Followell, when the natural being revolted against the conventions that deformed it, the corset, symbol of slavery that "add[ ed] to the natural inferiority of women," was "a new Bastille to be demolished."

O'Followell's eloquence bore testimony to the frustrations that the corset's adversaries encountered. But the Bastille was crumbling. In a few years, thanks to the war and to postwar fashions, it would be in ruins. The bicycle had played a great part in this; so had medically and socially inspired arguments for healthier bodies and more rational dress; so had the great couturiers, from Redfern to Paul Poiret. Unmoved by considerations of comfort or hygiene, dressmakers then as now concerned themselves with fashion--that is, with styles whose chief characteristic is that they go out of fashion. As Cocteau has said, "La mode, c'est ce qui se démode." The frills and flounces that had given women of an earlier age "the appearance of being composed of different pieces poorly fitted together" were discarded in favor of more fastidious harmonies; showy materials and garish colors fit for parvenus were replaced by discreet effects seen only by the eyesof connoisseurs. Proust's Marcel dressed his Albertine in subdued shades and materials that only an aesthete like Charlus could "appreciate at their true value."

Everything suggests that fashion remained equivocal as ever. Writing about the years when his clients replaced the corset with the brassiere, Poiret would boast: "I liberated the bust, but I hobbled the legs . . . Everyone wore the narrow skirt." In the same vein, the loosely pleated robes of Fortuny, admired by Proust's painter Elstir in Remembrance of Things Past, hung in natural folds and dispensed with corsets, but they imprisoned their wearers in heavy folds of brocade and silk. Conspicuous uselessness continued à Ia mode. The role of fashion in women's liberation remains uncertain. Still, La Nouvelle Mode of 1900 correctly noted a change: sports, diet, and hygiene had altered habits and manners. Women were trying to lose weight, they were eating less, they were crying less, they were fainting less. If women no longer suffered from the vapors, this may have been due to less constricting garb. It was certainly due also to loosening social constrictions. And to a changing image of themselves that was reflected in and by the images of fashion.